nota bene: if you want to skip to practical advice, start reading at the section titled “Place Yourself”

Table of contents

Open Table of contents

Why am I Writing This

Over the years I have had many conversations with people who find out how many languages I speak, and their responses usually fall into one of a handful of buckets. The most common is something along the lines of, “Oh wow! Some people are just made for languages,” or, “Oh, I could never, I wish I had started young.” Another is, “How do you find the time? Are you spending hours every day?” Usually I try to recommend to them the tools that I have used, and I spend time trying to convince them that with the right method they could learn another language too. However, I have the sense that I fail to adequately convey my ideas in those conversations, and I always feel a bit frustrated with how they go. This essay is my attempt to put all of my thoughts on the subject into one place, so that I can just point people to it in the future.

Imagine you decide to learn Spanish in your free time. Maybe you took a couple of levels of Spanish in school when you were younger. You had hopes that by conjugating enough verbs or memorizing vocabulary lists you would be dancing the tango (badly) and seducing everyone around you with your sweet, [insert Spanish-speaking country here] accent. You saw an ad for Duolingo that made you feel bad about yourself for not putting in the work you should have put in. You decide, “Okay, that’s it. I’m finally going to learn Spanish”. You download the app. You spend a few months building a streak by translating sentences like “Roberto sits on the platypus”. You feel good. You feel like you can finish those lessons quicker and quicker. Then you go to a taqueria and realize you don’t even know where to start in holding any practical conversation. Okay, no problem. You hire a tutor. You start doing homework every week and begin to speak. But it is painful, it is embarrassing and it hurts your brain. “I don’t have time for this crap,” you tell yourself. “Maybe if I had a year off I could finally dedicate the time and space I need to learn this.” You put it aside, yet again. You read some blog posts about how the optimal time to learn a language is when you are in the womb, or better yet, starting at conception. You scroll TikTok and see videos of people rubbing their success in your face. You feel dejected. Luckily, you happen to stumble upon this interesting blog called Christo Notes and see a post titled “On Language Learning”…

There are many people with many opinions on the “correct” way to learn a language. A lot of them post or make videos on the internet. If you are trying, or have tried in the past, to learn a language, I’m sure you have encountered some of this content. Some of it is narrowly useful, some of it is engagement bait, but none of it really gets to the heart of what really allows someone to be successful in learning a language. The short answer is that success is approximately proportional to quality time spent engaging with the language. Of course, saying that doesn’t really help anyone understand what to do, so I will try to give a longer, more nuanced perspective that can hopefully be of some use.

I speak from experience. As a native English speaker, I’ve learned nine languages. After taking my childhood Russian exposure to fluency, I added Spanish, German, French, Greek, Ukrainian, Bulgarian, Swedish, and Italian. My levels range widely: from functional tourist level in Italian (around B1 listening comprehension on the CEFR scale) to comfortably handling complex conversations and native media in Russian, German, Greek, Ukrainian, and Spanish. My French, Bulgarian, and Swedish sit somewhere in between.

With all of that out of the way, the first and most important thing to realize when learning a language is that it is not really a cognitive problem, it is more of a problem of organization and habit formation. Most people really can become fluent in a second language with enough quality time spent consuming and using the language. The key is to know what constitutes quality time.

Quality Time

What do I mean by quality time? Well, it differs depending on where you are in your journey. For simplicity, we can break things up into beginning, intermediate, and advanced stages. The beginning stage also has subcategories. You could have no experience at all in the language, not even understanding the writing system. You could also have a bit of a head start, for example if the language shares an alphabet with yours, or you had some classes a long time ago but retained (almost) nothing. Regardless of what stage you are at, we can define quality time as something like “time spent either consuming or producing the language at or slightly above your current level”. If you are a beginner this could mean learning the writing system or using some simple Duolingo-esque app. If you are intermediate this could mean listening to a podcast where you understand approximately 70% to 80% of what you are hearing. It could mean reading a news article and looking up phrases and words you don’t know. If you are advanced it could mean an hour-long session speaking to a native speaker about anything that interests you. The point is that the time you are spending needs to not be a complete waste of your energy or resources.

Some examples of time spent that is (usually) a waste include: reading a chapter of a grammar book (unless you really enjoy it), using Duolingo if it has already become easy for you, speaking to a structured tutor who has you do weekly assignments, filling in sentences and vocabulary lists, etc. What all of these activities have in common is they don’t match the language input (or output) with one’s current level in the language. You want to be putting in time in a way that allows you to consume or produce the maximum amount of words and sentences of actual genuine content in the language.

Total Time Spent

This part is the easiest to explain, and the hardest to implement. Success can be thought of in roughly these terms.

There are a lot of factors that go into determining how much time you spend learning a language, but the biggest factor by far is how much you enjoy doing it.

In the beginning stages, enjoyment can come from more mundane activities, like vocabulary flashcards or gamified apps, since most of what you are encountering is new and it feels exciting to embark on the journey. You can easily create a habit for yourself of spending 10-20 minutes per day devoted to the language, and things feel easy and great.

Then you hit a wall around 4 months in. You don’t know what to do. The things you are doing are too easy and starting to get boring. Harder content is way too difficult. You see no way how to get from A to B. You quit. Again.

I will spend quite a bit of time explaining how to specifically overcome this, but it really does boil down to finding ways to make consuming authentic material fun and novel.

Place Yourself

Now that we have established the importance of quality time and total time spent, we can move on to some more practical advice.

Where do you fall?

Super beginner: no experience, target language is very different from your native language. Examples include English speaker wanting to learn Japanese or Arabic. Mongolian speaker wanting to learn Igbo. You get the idea…

Beginner: little to no experience, target language is the same alphabet as your native language. Examples include English speaker wanting to learn Spanish, Russian speaker wanting to learn Bulgarian, etc. Maybe you have spent a little time with some language learning apps and can understand basic sentence construction.

Intermediate: This is a wide range, and pretty vague. This is where most dedicated, organized people end up falling off. If you can read simple sentences and articles and understand them without translating every single word, you are probably here. At the higher end of this range is the ability to listen to podcasts and pretty much follow most things, but easily lose track on super native authentic content that is fast. Maybe you can understand most things that are said to you, but when you watch a TV show or a movie in the language you get lost, but can follow a bit if there are subtitles.

Advanced: At the advanced level, you probably won’t get much from reading this essay. So I will just emphasize that at this stage it is all about consuming the maximum amount of enjoyable content. Watch movies, talk to native speakers, write essays, whatever you want to do, just keep doing it. Actually, you will find that this advice isn’t that different at a high level from the advice I give to intermediate learners, but the specifics matter a lot for how to actually implement it at each level. The intermediate stage requires a bit more creativity and guidance, whereas advanced learners have maximum freedom to enjoy whatever they want.

In the Beginning was the Word

Now I will guide you through the entire process in a way that closely mirrors how I have done things myself, from the super beginner level through upper-intermediate/advanced, so that things are a bit more concrete in your mind. I am going to use the example of learning Greek, because I love Greece and the Greek language is one of my favorites. Πάμε, φίλε.

Since the Greek alphabet differs from English, step 0 is to learn the Greek alphabet. You can use a flashcard app for this, or just Google your way through it. You probably won’t get stuck here, most people don’t. The goal is to be able to sound out words by the end of this stage. It doesn’t matter how accurate your pronunciation of them is. At all. If you can kinda sound things out, you are ready to move on.

Step 1 is getting the basics down. This means some basic vocabulary, and putting sentences together. Very rudimentary stuff. The goal of this stage is to basically get the knowledge that one has after taking a few language courses. You can use any of the popular apps out there for this. Duolingo, Memrise, Babbel, whatever. The end result is usually pretty similar for people after using these. Depending on the language, you should only spend anywhere from 2 weeks to 1 month on this stage. If you spend longer in this stage, you are probably moving into the territory of wasting your time. That is why you see videos on YouTube with titles like “Learned Spanish on Duolingo for 400 DAYS: AM I FLUENT????” Spoiler alert: none of them ever are.

Okay, you have the basics down. Now what? What you do now (step 2) is locate some beginner content that is actually spoken by native speakers of the language and is a bit longer-form. It is vital that you find something with both audio and text. My favorite resource for this is the app LingQ (I am not sponsored by anyone and my recommendations are purely my own). You can also purchase a “graded reader”, which is a book that uses material targeted towards learners. I have never done this since LingQ removes the need for it, but I have heard good things about things like Assimil, and I believe the well-known polyglot Olly Richards has some great books that are collections of simplified short stories. The short story format is ideal for this stage, and LingQ also has (at the time of this writing) a series of “mini stories” that are perfect for this purpose. Browse around and select the resource that you like the best, and you are ready to start using it. Podcasts can also be very helpful, especially if they are categorized by learner level. Some great ones I have used include Podcast Italiano, Russian Progress, Russian with Max, Easy German, Simple Swedish, and many others. They are great specifically because they have content categorized into levels, so you can filter by beginner episodes, and they also have transcripts, which is non-negotiable at this stage.

Now that you have the material, you start consuming it. The way that I approach it is by reading and listening to the material at the same time, pausing (very) often and rewinding whenever I don’t understand something, translating it using a translation tool (DeepL or any LLM like ChatGPT serves this purpose exceptionally well), and continuing on when I understand. I usually go sentence by sentence, methodically. This should be pretty slow going in the beginning, but it shouldn’t feel impossible. If it feels impossible, you might revisit step 1 for a bit.

Below is an example simple Greek sentence in one of the mini stories on LingQ.

The way that I would approach this is by listening to it and following along. Notice how I have the translation of the sentence open simultaneously. I usually pause the audio, read the English translation first, then play the audio and try to follow along by reading the Greek. If I didn’t understand the word μάθετε, I look it up individually. “Ah, it means ‘you learn’, okay.” Move on. I notice that it differs a bit from English, in that the literal word-by-word translation goes something like “you want to you learn another language”. Interesting. I take note of that grammar, and go to the next sentence. Maybe I will replay the audio another time through now that I have the pieces put together. Once I feel good about this sentence, I will move on in the audio. Once I have listened to/read through the entire story, I will usually go through it again without stopping (especially in the beginning stages of this process).

The way that I would approach this is by listening to it and following along. Notice how I have the translation of the sentence open simultaneously. I usually pause the audio, read the English translation first, then play the audio and try to follow along by reading the Greek. If I didn’t understand the word μάθετε, I look it up individually. “Ah, it means ‘you learn’, okay.” Move on. I notice that it differs a bit from English, in that the literal word-by-word translation goes something like “you want to you learn another language”. Interesting. I take note of that grammar, and go to the next sentence. Maybe I will replay the audio another time through now that I have the pieces put together. Once I feel good about this sentence, I will move on in the audio. Once I have listened to/read through the entire story, I will usually go through it again without stopping (especially in the beginning stages of this process).

That flow of reading, listening, pausing, translating, rewinding, reading, listening, etc. is very powerful, and it will take you very far. Continue to do this for as much of the graded reader (or podcast) content that you have at your disposal.

Moving to Intermediate Stages

LingQ usually has about 50 of these mini stories, and they gradually increase in difficulty from mini story 1 to mini story 50 (at the time of this writing of course, I really hope LingQ continues to exist for a long time, but if they don’t the advice still applies to whichever beginner content you are consuming). I find that systematically getting to story 50 and feeling good about my understanding of the content usually takes several months. Regardless of how long it takes you, once you reach the point that you are understanding basic dialogues and stories with some complex constructions with ease, you are probably in the intermediate stage.

The intermediate stage is around the time when the novelty of learning the language will start to wear off. You won’t get as many dopamine hits for piecing together new constructions as you did in the beginning. Luckily you should have by now built up enough of a routine to keep going, but the routine itself is just the framework, it is not enough to maintain the passion and the fun, which is the real trick. The mind will crave more interesting content, so the next step (step 3) is to actually start finding some of this content.

If you have already been consuming content from a podcast, chances are they have some more intermediate content that might be of interest. This is the case with the podcast “Easy Greek”. In fact, I am a huge fan of the Easy Languages people in general, they helped me significantly with their YouTube channel and podcasts. I made extensive use of Easy German, Easy French, Easy Italian, Easy Spanish, Easy Greek, and Easy Russian. You can do your research to find what interests you. The important criteria to keep in mind for finding intermediate content is that it should have audio and text, it should be fun for you to listen to, and there should be a lot of it. To help you in your research, you can use terms like “greek language intermediate podcast”, “greek language comprehensible input”, etc.

That same workflow that we discussed for the beginner stage applies in the intermediate stage as well. Read, listen, pause, translate, rewind, read, listen. Rinse and repeat. This is your vehicle to mastery. This is the key mechanic that enables you to get to fluency. Don’t listen to any of the people that claim reading translations doesn’t work. It does.

You can also start to broaden your content consumption in this stage. Music, podcasts that don’t have transcripts, movies, TV shows, arguments with people on social media, whatever interests you. Just make sure that most of your time is spent with material that you can understand with a text and translation. The other fun stuff is essential, but in an indirect way. It gives you a barometer on your progress (you might notice “Oh wow I actually understand like 50% of this movie whereas before it was 10%”), and it gives you motivation to continue consuming content. Listen to songs by Dimitris Mitropanos and sing the lyrics in the shower, even if you don’t understand. The beauty of the art is motivating. It gives you the energy to continue. Find Greek people, say Τι κάνεις. They will embrace you at the slightest effort. This stuff is definitely important.

Pushing Through the Plateau

There comes a time in learning any language when progress gets harder to see. This is about that time. You have a routine that you follow every day, you enjoy the process most of the time, but you no longer feel like you are improving at the same rate that you were in the beginning. This is when most people tend to drop the habit, move to other things, and decide that language learning isn’t for them.

Don’t.

Do NOT drop the habit. If you reach this stage (which I separate into its own, step 4), it is actually a sign that you are on the right track. It is hard to believe, but I promise you if you push through this period of intermediate-level indefinite learning, you come out the other side with a very high level of competency. The problem is that this stage is by far the longest stage in the process. It can take many months, and sometimes even years, until you wake up one day and realize that you have made much more progress than you think. Part of the reason that I have been able to learn so many languages is I accidentally passed through this stage with Russian and made the realization that I can do it with any language I wanted.

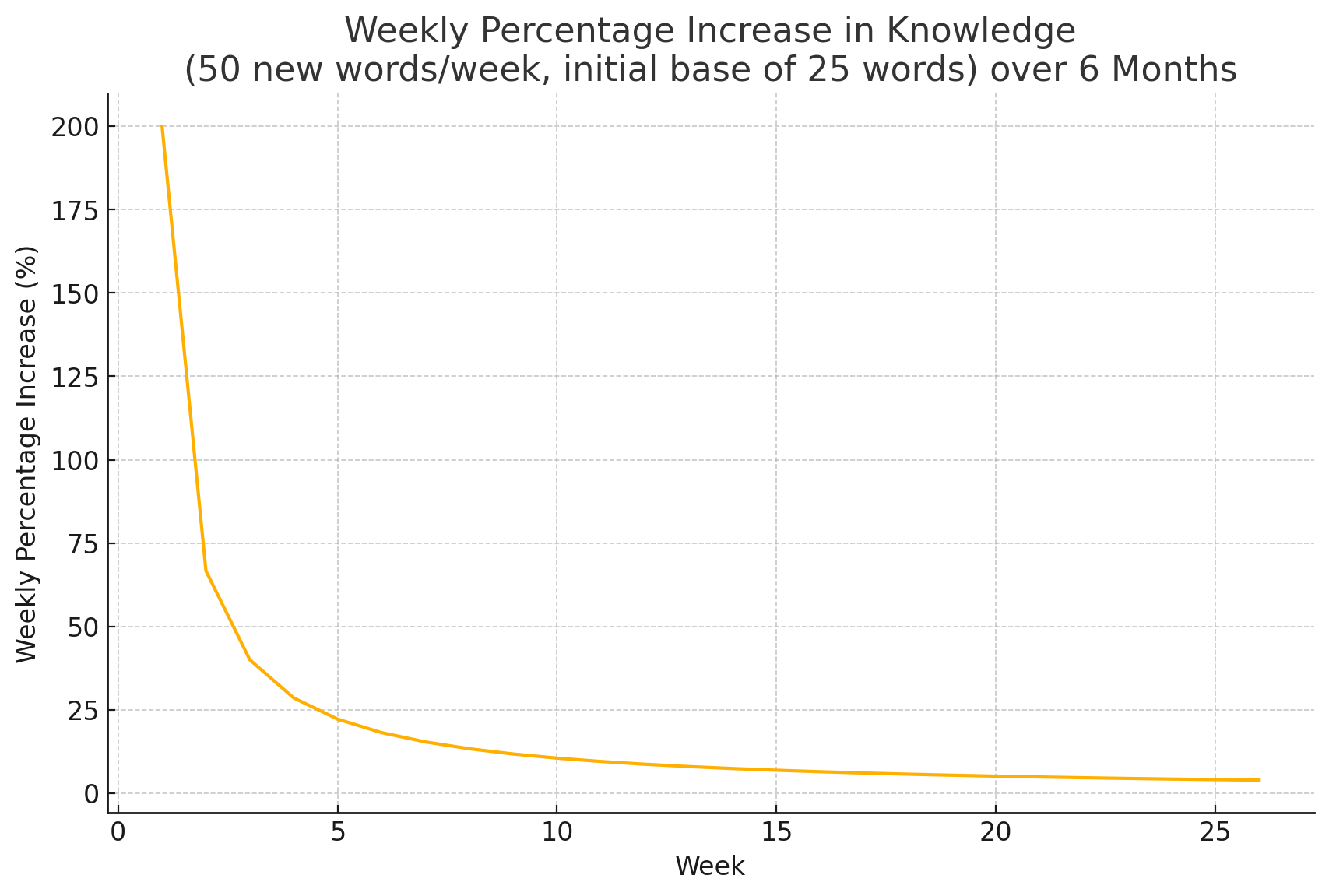

I believe that this stage is the most difficult of all. The reason is that it is a bit of an illusion. Consider months 1 through 3. Your percentage improvement over time is massive. You are improving somewhere from 200% to 400% every single week in the beginning because your knowledge base is so small. As your knowledge base increases, however, your percentage gains per unit time are going to decrease, until they start to become unnoticeable from week to week. If you learn 50 new words and phrases in a given week, every single week, your percentage of knowledge gained is going to look something like this:

Obviously this graph is simplified, since progress doesn’t move at a constant linear rate, but the principle remains. This is a recipe for burnout and reduced motivation if you don’t realize it is all par for the course.

Obviously this graph is simplified, since progress doesn’t move at a constant linear rate, but the principle remains. This is a recipe for burnout and reduced motivation if you don’t realize it is all par for the course.

The key to pushing through this stage is to have it be as fun and motivating as possible. Maybe you could plan a trip to a country where the language you are learning is spoken, maybe you could watch some more movies, more TV shows, more music. Maybe you could start to tackle a classic novel in the language that you have always wanted to read. Anything that you really enjoy to give yourself that motivation to spend doing the main learning activity (reading and listening simultaneously). There are basically two tracks here. The fun stuff, and the serious stuff. They are self-reinforcing. The fun stuff is what gives you the power to want to do the serious stuff, and actually makes the serious stuff a bit more fun. The serious stuff gives you the power to have more fun when doing the fun stuff, and the virtuous cycle continues.

One of the best motivators for me personally is finding native speakers to speak with, which leads me into the next stage (step 5).

Speak!

There are many opinions among online polyglots about when the right time to begin speaking is. Sometimes the topic can get quite divisive. The correct answer to the question is to begin speaking whenever you feel that you really want to, and when you feel like it will enrich your experience. Cop out, I know, but it’s true. It will differ person by person, depending on how outgoing you are, how comfortable you are with making mistakes, what topics interest you, any specific timelines for vacations one might have, etc. For me, this tends to fall right in that intermediate plateau, when my motivation starts to dip, when I have exhausted my internal curiosity and feel that I need some external motivation.

So how to proceed? If you know people in your life that speak the language, you could always strike up conversations with them, but in my experience the best thing to do is to find a native speaker tutor online who you can have 30-minute to 1-hour conversations with 1-3 times per week, depending on your intensity level. I have personally used the website Italki to find tutors, but I am sure other good ones exist. The main point is to find someone to have casual conversation with for 30 minutes to an hour on topics that interest you. The tutor doesn’t have to have any special certificates or qualifications from university. In fact that can actually be an impediment to progress, since they will want to bog you down with homework and exercises, which are useless. The main things to look for are native speakers that also know your native language. So in our example I would search Italki for tutors that are from Greece and also know some English. Knowledge of your native language can be helpful because they can correct you and explain things to you more effectively in your language. It speeds things up, but it is not essential.

I like to start with 30-minute conversations in the beginning, and gradually move to 45 minutes, and eventually to 1 hour. 1-3 times per week is enough to keep progress moving at a good pace.

A side effect of starting to speak is that you will now have a new axis upon which progress will start to show really quickly, which is motivating. Just as your motivation from input is decreasing, you will start to get new dopamine hits from improvement in your output. Just ride that wave, continue having conversations, continue consuming native content, and you will eventually be good enough to call yourself fluent. That is really it. Now to address a couple points that tend to come up in conversations with people.

What About Grammar?

You might be wondering why I haven’t addressed grammar yet. Surely it is important to understand grammar? How can one learn a language without understanding the structure? I agree. It is important to some degree. The reality, however, is that grammar explanations tend not to stick until you have some sense of the language. It is a bit of a catch-22. The way I approach grammar in my language learning is as follows:

If, when reading and listening, I translate something, but don’t really understand how the translation maps to the original, despite translating the phrase, segments of the phrase, and each word individually, I will try to research the grammar of the phrase a bit. I didn’t have ChatGPT (or Gemini or Grok etc.) when learning most of my languages, but from now on I believe it is the best way to research grammar questions. The point is to learn just enough about it so that you can understand the phrase that generated the confusion. Once you have that, move on. There is no need to note it down or to spend any time trying to memorize it. You will forget it, and that’s okay. Just research it again when it comes up. This way you are learning grammar in a bottom-up fashion rather than a top-down fashion. A lot of the uselessness in language courses comes from the top-down approach, where students end up front-loading a lot of material that is important, but has no practical experience to solidify it in the mind. Our minds are meant to go from practical experience to theory, not the other way around.

I also disagree with the people who say one shouldn’t do any grammar study at all. Learning grammar in the way I described, bottom-up, is actually a great way to solidify some of the knowledge that you are taking in, and helps you see patterns more quickly in the future.

Pronunciation?

You don’t have to start speaking with a tutor before you can start to get good at pronunciation in a language. In fact, I often impress tutors with my ability to pronounce the language in my very first lessons with them because I am a bit obsessive about it. If you exert about 10% of the effort I am about to describe, then you will probably get quite good at it too. Basically I just talk to myself over and over again. While I am reading, while I am listening, in the shower, before bed, you name it. I mimic people in the audio that I listen to. I repeat words and phrases over and over until I am satisfied with every aspect of it. I really do just repeat myself out loud until the sounds I produce sound close enough to the sounds I am hearing. If you do this for years you will be good enough, trust me, trust the process.

Age

You have probably heard that young children learn languages best, and our ability to learn languages decreases as we get older. This point of view gets me angry because it is so useless, and at the end of the day quite debatable. The only part that might be true is in our pronunciation. Steve Kaufmann, a well-known polyglot and creator of LingQ, started learning Russian when he was 60. So stop making excuses and just see what kind of progress you can make by following the method outlined above. If you really follow all of this advice for years and get nowhere, then reach out to me and maybe we can discuss.